Incidence & prevalence

Types of AAV

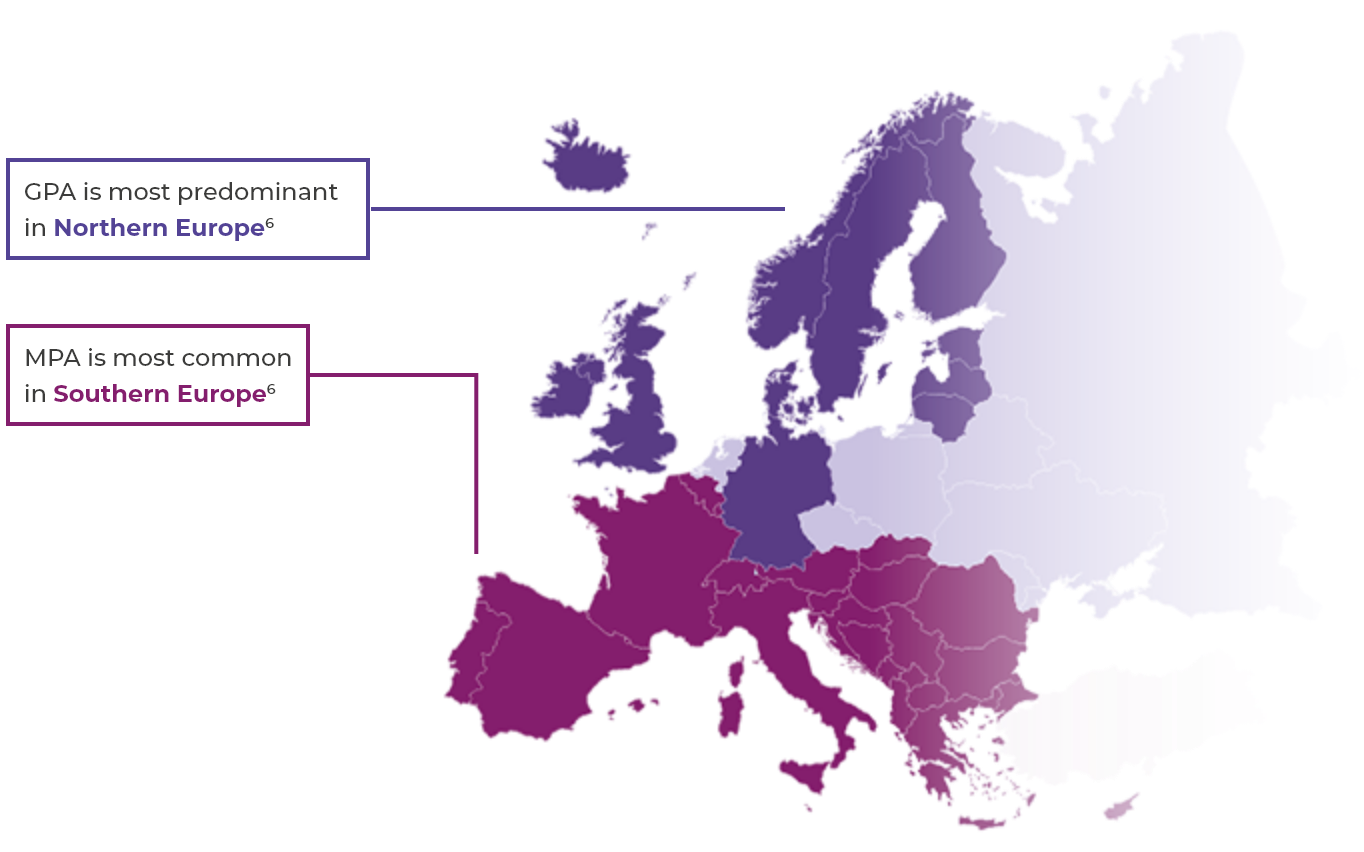

The two most common subtypes of AAV are granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, previously called Wegener’s) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). The other subtype is eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, previously called Churg-Strauss syndrome).2,3 This website will focus mainly on GPA and MPA.

AAV is a rare disease2

- Global prevalence: 30–218 per million4

- European incidence: 13–20 per million per year2,4

AAV occurrence

- AAV can affect both younger and older people, but is rare in children and young people and incidence rises with age2,5

- AAV occurs slightly more frequently in men (annual incidence rate approximately 60%) than in women2,5

Systemic organ damage

AAV can result in systemic organ damage and failure, with the kidney and lung as major targets1-3

AAV can result in damage to vital organs such as the lungs, kidneys, nervous system, gastrointestinal system, skin, eyes and heart.3,4 Both GPA and MPA show a lot of clinical commonality, whereas EGPA is distinctly different.2

As many as 23% of PR3- and MPO-ANCA positive patients who require RRT at the time of diagnosis die within 6 months and 29% do not regain renal function.5* In patients with renal involvement at diagnosis, ESRD occurs in 13% of PR3- and MPO-ANCA positive patients within 3 years of diagnosis. Compared with a short prodromal phase, patients with a long prodromal phase (>22 weeks between first AAV symptoms and diagnosis) are more likely to have proteinuria present at 6 months and are at double the risk of 3-year ESRD, which underlines the importance of early diagnosis in order to improve renal outcomes.6†

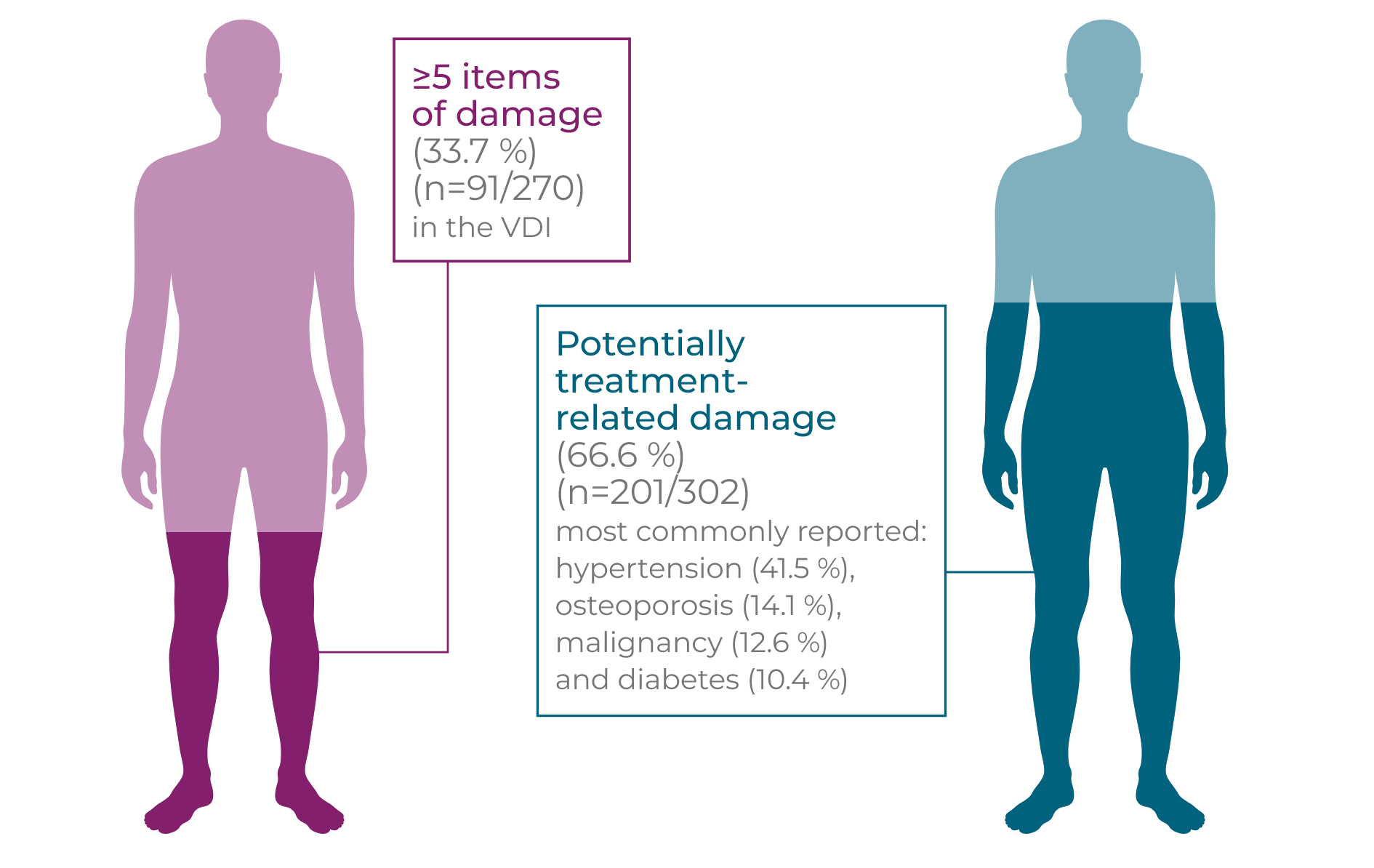

GPA and MPA patients accumulate organ damage from a combination of vasculitis activity and glucocorticoid-related AEs1–3

Long-term and repeated high-dose glucocorticoid use is associated with an increased risk of new onset/worsening of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis of bone, malignancy, cataracts and other debilitating side effects.1,2*† In a study following newly diagnosed GPA and MPA patients for up to 7 years, the frequency of damage, including potentially treatment-related damage, rose over time (p<0.01). Patients initially experience early increased damage following diagnosis (n=270), with 81.5% of patients experiencing ≥1 item in the VDI at 6 months compared to 24.4% of patients at baseline, with renal (proteinuria and GFR <50 mL/minute) and cardiovascular (hypertension) damage the most frequent. Severe damage, a VDI score ≥5, increases over time and at long-term follow-up 33.7% of patients had severe damage. Hypertension was the most commonly reported item at long-term follow-up, demonstrating an accumulation of cardiovascular damage over time. At baseline, 4.8% of patients had hypertension. Within 6 months, this rose to 17.0% and at long-term follow-up 41.5% of patients had hypertension (p<0.01 ).2†

High levels of long-term vasculitis damage were independently associated with increased cumulative glucocorticoid use (p=0.016).3†

This serious morbidity is accompanied by a significantly increased long-term mortality risk, with a hazard ratio of 2.41 (95% CI: 1.74–3.34) in GPA patients compared with age- and sex-matched controls.2–4†‡

At a mean of 7 years post diagnosis in patients with GPA or MPA…2†

Mortality & morbidity

AAV leads to an increased risk of mortality, especially in the first year after diagnosis1,2*

In the first year after a GPA or MPA diagnosis

(n=524), the mortality rate is 10.7% (n=56)1*

(n=524), the mortality rate is 10.7% (n=56)1*

Of these patients

Half (50%) of mortality in the first year is due to treatment-related infection1

In clinical trial settings, the cumulative survival rate at 2 and 5 years in patients with newly diagnosed GPA and MPA is 85% and 78%, respectively.3†

Population-based data suggest that the long-term mortality rate in patients with AAV has improved considerably over the past two decades, but is still not as good as matched controls.2‡

In a study following individuals for a median 5.2 years, the mortality rate in incident GPA or MPA patients receiving current treatment was 2.6 times higher than an age- and sex-matched general population (p<0.0001).3†

Referral, diagnosis & follow-up

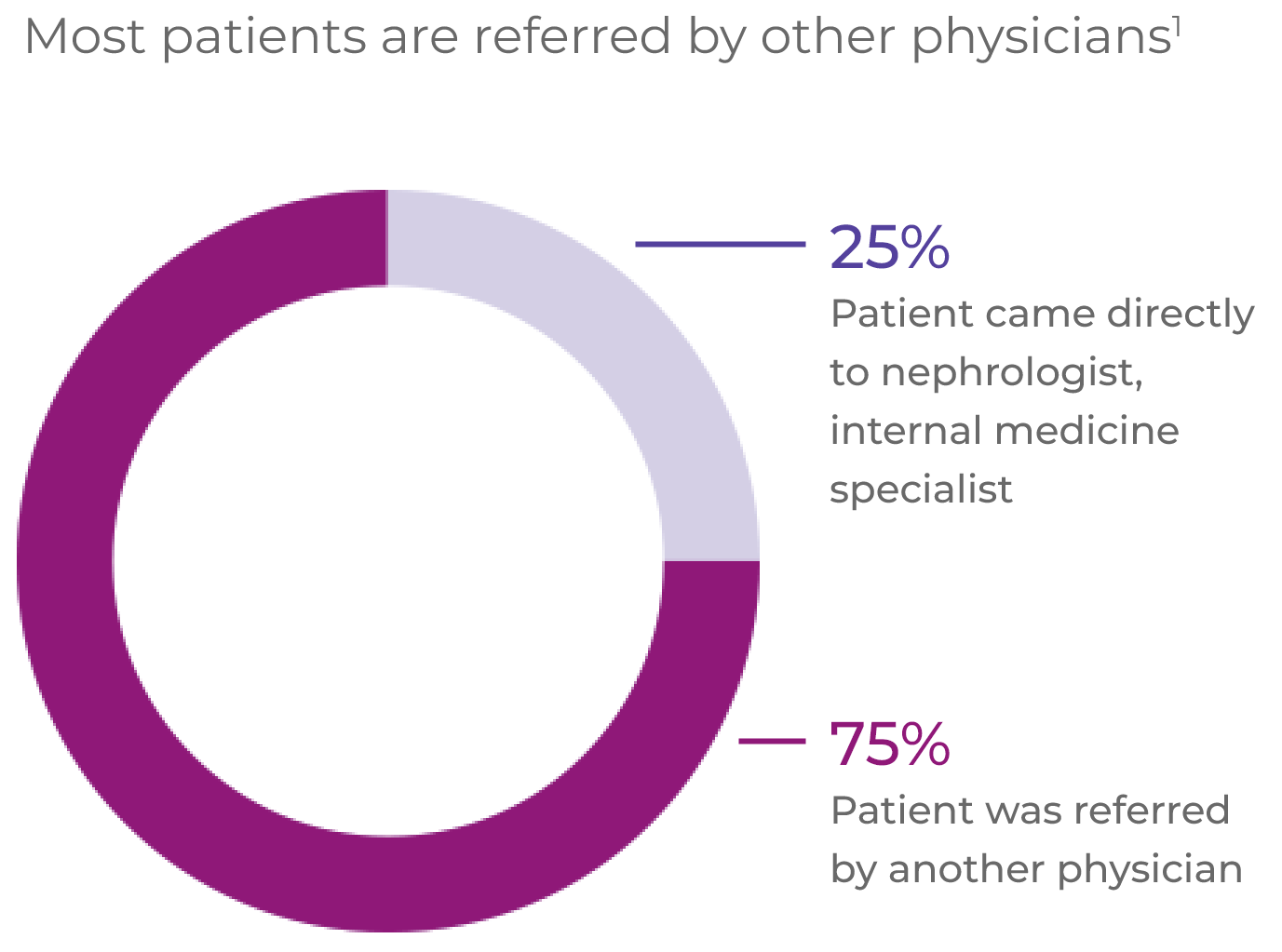

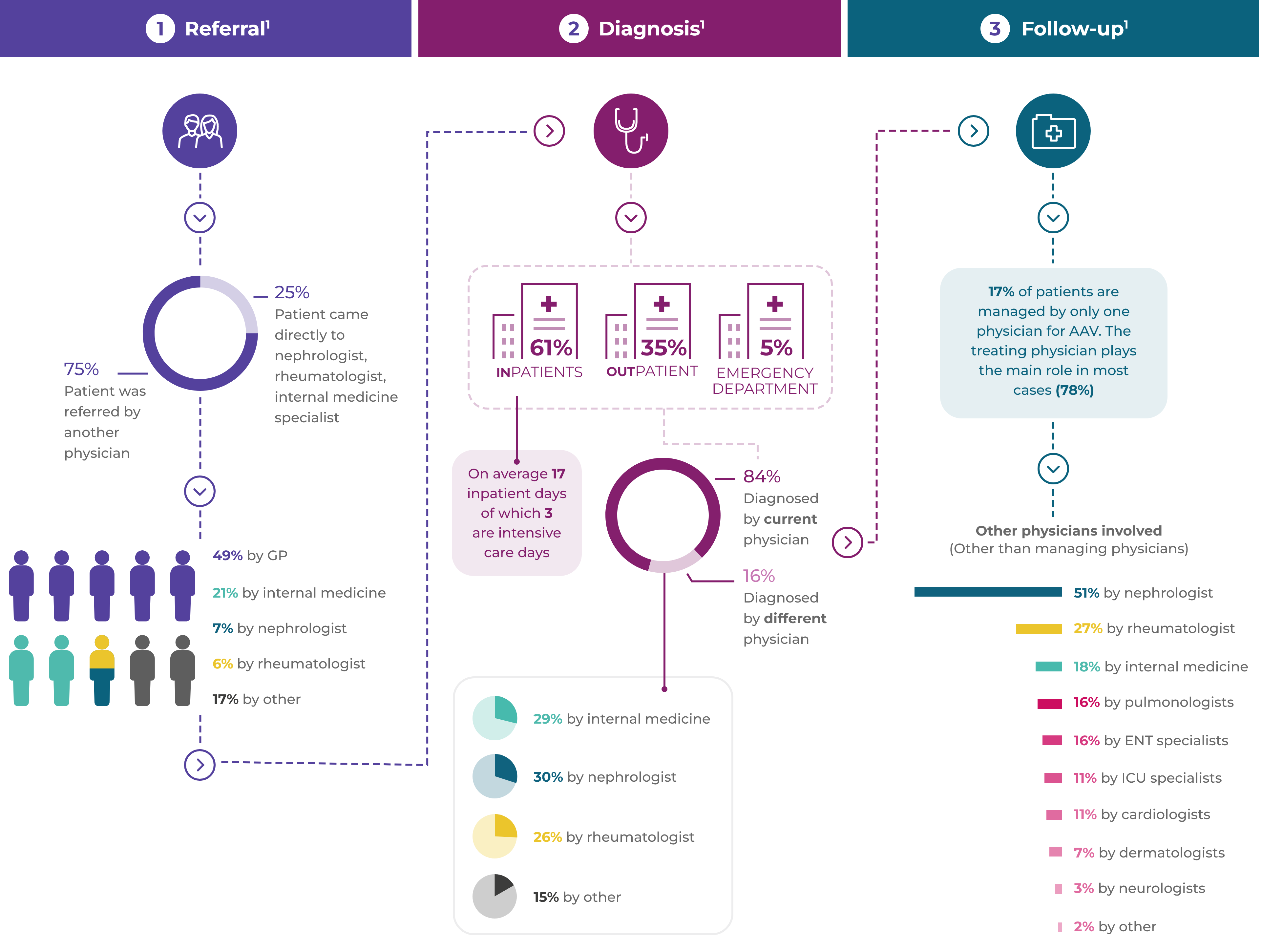

AAV patients often experience a complex pathway of patient referral and diagnosis1*

EULAR recommendations state that patients should have access to education focusing on the impact of AAV and its prognosis, key warning symptoms and treatment (including treatment-related complications). AAV requires multidisciplinary management by centres with, or with ready access to, specific vasculitis expertise.2

Many patients have renal disease at presentation, but general non-specific referral symptoms predominate1

Renal disease:64%

Fatigue:58%

Fever:54%

Weight loss:53%

Joint pain:47%

16% of patients have had their referral symptoms for over

3 months before receiving an AAV diagnosis1

Comorbidities at diagnosis are common (65% of patients)1

Hypertension:45%

Type 2 diabetes:16%

COPD/asthma:15%

Coronary arterial disease:10%

Arthritis:9%

Osteoporosis:7%

BMI >35:6%

Cardiac failure:6%

The relative rarity and non-specific presentation of AAV can lead to a delay in disease diagnosis of more than 6 months in one-third of patients.3

Diagnosis of AAV and differentiation into the GPA, MPA or EGPA subtype depends on the patient’s clinical symptom constellation, the results of imaging studies and laboratory investigation.3,4

Due to the linkage of anti-PR3 with GPA and anti-MPO with MPA, ANCA testing is critical for diagnosis.3–7

- Up to 20% of GPA and MPA patients and over 60% of EGPA patients are ANCA negative4

- A positive ANCA test result can be found in other conditions, e.g. autoimmune hepatitis, ulcerative colitis, infection with hepatitis C virus or HIV, or infectious endocarditis, without associated vasculitis4

An organ biopsy, usually renal, is often performed to confirm the diagnosis.3,4

Referral

Diagnosis

Follow-up

Introduction to AAV

AAV is a rare, severe small vessel vasculitis that affects multiple organs and has a high acute mortality risk1

Read more

Disease mechanism

The interaction between the activated alternative complement pathway, neutrophilsand C5a is at the heart of vasculitic damage in AAV2

Read more